Medical & Dental Care Solutions.

We’ve 25 Years of experience in Medical Services.

Medical & Dental Care Solutions.

We’ve 25 Years of experience in Medical Services.

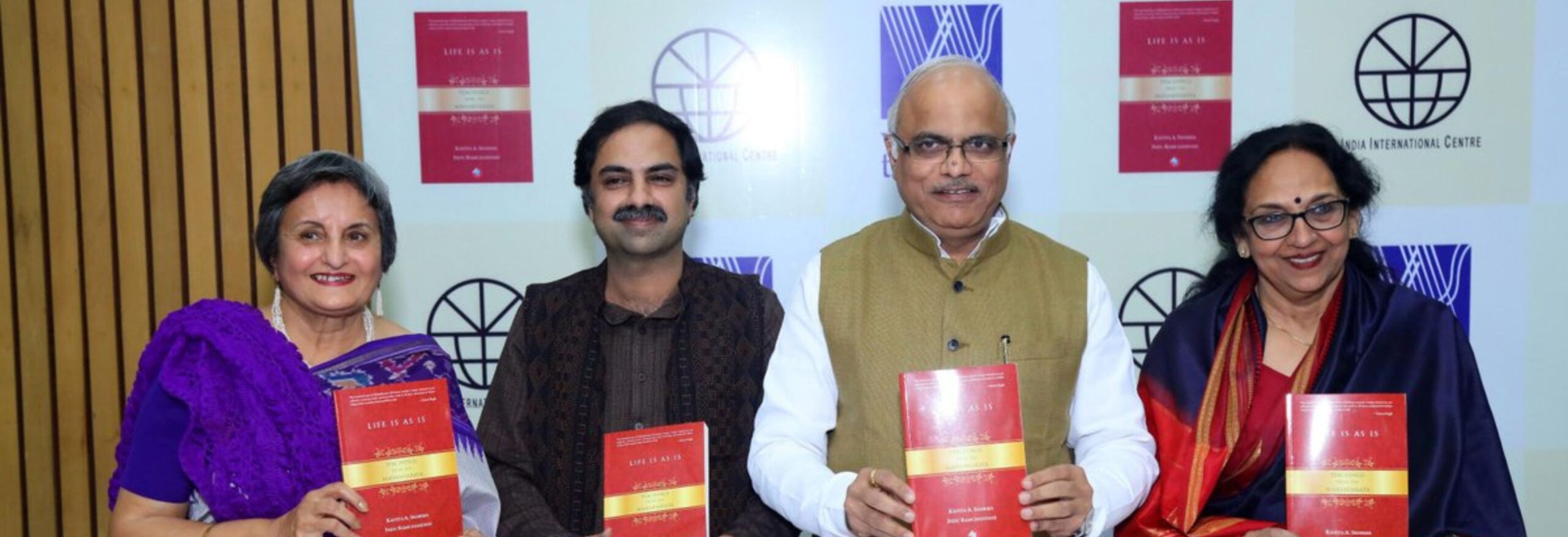

Dr Kavita A Sharma

Former President, South Asian UniversityAn accomplished academician, Dr. Kavita A Sharma has been an active contributor to the cause of higher education through her teaching, publications and the institutions she has been associated with. Dr. Kavita Sharma started teaching in 1971 in Delhi University’s Hindu College and became its Principal in 1998 and served there till 2008 when she took up another challenging assignment as Director of India International Centre, New Delhi.

Dr Kavita A Sharma(Former President, South Asian University)

An accomplished academician, Dr. Kavita A Sharma has been an active contributor to the cause of higher education through her teaching, publications and the institutions she has been associated with. Dr. Kavita Sharma started teaching in 1971 in Delhi University’s Hindu College and became its Principal in 1998 and served there till 2008 when she took up another challenging assignment as Director of India International Centre, New Delhi.

My Educational Qualifications

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI

B.A. (H) English

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI

M.A in English

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI

Ph.D in English

UNIVERSITY OF DELHI

LL.B

UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA

LL.M

Family Members

Professor Lalit Prakash Agarwal

Dr. Savitri Agarwal

Parijat Sharma, Archana Rana, Trayi and Viraat

Molshree A. Sharma, James Hegbrg, Maya

Our Books

Ready to get our medical care? We’re always wait for serve you, Make an Appointment.

Best Medical & Health Care Near Your City

We’ve 25 Years of experience in Medical Services.